As a third option between gathering the technical knowledge (and paying money) to run your own social network or paying someone more money to host your social network, I think the public library is in a prime position to mitigate drawbacks and make the process of creating small Fediverse instances a still-easier process for a member of the curious public, and to do so at no additional costs than what they already pay in taxation to support public libraries.

Why A Public Library?

For U.S. audiences, there's probably a public library within a short commute of where you are, and many public libraries are actively looking for ways that they can do local projects, or projects with primarily local impacts. By trying to attract people from the local area with specific interests, rather than from across the world, public library-hosted instances can also help keep numbers down and avoid overburdening moderators and admins with more people than they want to manage.

Most public libraries are also staffed with IT personnel who have command-line comfort, have server infrastructure, and have gone through the process of getting and maintaining domain names and certificates. And, perhaps most importantly, the IT staff at a library are usually getting paid to do all of these things through public support and funding, so there isn't a worry about whether the tip jar will have enough in it to cover costs for another month.

Finally, libraries are at least nominally interested in the privacy and security of their users, so being able to offer an alternative to the algorithm-driven rage-machines that are overrun with ads and that suck data to their own nefarious ends definitely has an appeal.

So let's update the proposal from the beginning of the talk to encourage the idea that one Fediverse instance is better than none, but what would be even better is if the public library could provide the infrastructure so that _many_ instances can be spun up by the public and their interests.

This idea is not all sunshine and roses, unfortunately. As much as I would like to say that every public library has the staffing, capacity, and infrastructure to be receptive to the idea of making Fediverse instances, that's not necessarily true. A proposal such as this might have to come with some sweetening of the pot where there's grant funding to pay for additional infrastructure and time, or a company will provide free hosting to a library up to a certain point of space and/or time so that a cash-strapped library can still experiment and offer something to their community.

There may also have to be some advocacy work from people both inside and outside the library to get this program off the ground. Some libraries are suspicious of anything that involves technology developed in the 20th century, much less anything being worked on in the 21st. Winning them over with the potential of having local people doing local things may take more than one meeting, more than one comment period, and more than one staff person to bring into existence. Showing that there's a interest from multiple communities in your area makes a library board and administration more likely to pursue a partnership or a proposal.

Next, depending on the setup of the instances, a library might be required to retain anything created on their servers or with their resources for a specified period of time and make that data available to a properly submitted public records request or law enforcement demand, including any data that the person who sent it might have believed was private. Figuring out how to offer a service and maintain maximum user privacy is an important discussion, and the library may have counsel who can help with those discussions and make recommendations to achieve these ends, once you have convinced them it is a good idea to try, but the usual warning about how nothing is ever truly private on an instance you don't own is still in effect here.

Related to data retention is the people problem. For as much as we'd all like to live in a place where our neighbors and ourselves are ideologically compatible, or at the very least, if we're not, we can politely ignore each other or disagree in productive ways, most communities have (or may attract) at least one jerk or troll who will want to use the network for behavior that is against the library's rules of conduct and/or applicable laws. Someone has to take out the trash when that happens, and determining who is responsible for that and writing into existence what procedures need to be followed to achieve that end will be important.

[After this presentation was given, with the explosion of Fediverse instances not showing much signs of stopping as people joined big instances and then started spinning up their own when .social and other large places were still giving them the same problems they had experienced on Twitter, Denise Paolucci, a founder of Dreamwidth Studios, wrote up a short guide about an instance administrator's potential obligations to avoid legal liability for someone running a Fediverse node in the United States with regard to items like Digital Millenium Copyright Act takedown notices, child sexual exploitation material, the requests of foreign and domestic governments for data and posts of citizens and residents of their countries, the Stored Communications Act, the Children's Online Privacy Protection Act, the General Data Protection Regulation, the Digital Services Act, the California Online Privacy Protection Act, FOSTA/SESTA, and other things. It's not a legal guide, because not a lawyer and not legal advice, but there's a good chance that the library, or the library's counsel (and they have counsel, believe me) is already familiar with all of these obligations and has structures in place for them. Denise's post is illustrative, however, about how much goes into running your own social site that isn't immediately obvious. For someone who has reasons not to want to roll their own, having the library provide a lift could be the difference between full participation and none at all. But it will also mean having to hammer out what happens when content that falls under these jurisdictions appears on the timeline, or worse, is posted by a user who believes their speech rights trump any and all other considerations. Having a process in place to handle it, knowing who is going to be handling it, and making sure that nobody stares into the abyss for too long are extremely important things.]

Finally, the library person who you start an idea with may not be the library person you finish an idea with. There are very few Benevolent Dictators For Life in the library world. Promotions, transfers, new jobs in new systems, retirements, and the like happen frequently, so at any phase of development, there may be an entirely new person who has to be onboarded at very little notice. Which might also require a pivot from your current reason why to do this to an entirely new one, as well.

There are also bigger issues you might encounter when making a proposal to your public library about adding Fediverse capacity. If there are enough instances spun up by enough people, eventually someone's going to hit on a great idea or become a local celebrity (or a Fediverse celebrity) and their instance is going to skyrocket past the Kazemi Kap. What happes then? Whatever the answer to that question might be, having a plan for the eventuality that somoene is going to hit it big is important to work out.

There's also the question of what the end goal of federated social networks is. If the point is decentralization and spreading things out so that everyone who wants one can get one and control it, then we're back at the biggest drawback: only those who have the skills and the desire will do the thing, and the rest of us will either have to find someone compatible or go without. If, as Alyssa Rosenzweig posits in "The Federation Fallcy," decentralization is already a lost cause and people will centralize naturally because that's where their friends are, the proposed solution is to democratize the situation, and produce governance accordingly that allows the members of the democracy to guide and shape policy and procedure. Democratization has failure points, as many of us in this timeline have seen, and one of the most pernicious ones is where a committed minority can gain outsize power through their commitments and reliance on a mostly apathetic or uninterested population not stopping them from grabbing and consolidating power until it s too late. We can see a sterling example of a minority exercising outsized power by reading PEN America's report "America's Censored Classrooms," about proposed and passed legislative bills in the United States that demand many aspects of education abandon reality and instead substitute a hagiographic fiction to be taught as the official history or position. One potential counter to democratization creating a mob or allowing a minority to take over is to produce a "civil service," as it were, that is ideally meritocratic and technocratic (even if in practice both of those are impossible) and operates by putting people with appropriate credentials and skills in places that are insulated from the winds of politics and giving them a set of independent professional ethics to operate from. Library workers and educators are both trying to position themselves as these professional, ethical technocrats an an attempt to insulate themselves from the howling and often contradictory storms outside, but the act of turning over decisions about education and what books are stocked in the library to the trained, knowledgeable professionals is often the very thing the outsize minority groups decry as fundamentally undemocratic. Thus, decentralization is proposed as the solution to professionalization and the argument loops again.

This tension also manifests in questions about whether the ethics of public libraries and FLOSS allow for decisions to be made at the code level about how the resources and tools get used. Historically, public libraries and FLOSS have been aligned in their thinking, adopting the position that it is the person using the tool, rather than the tool itself, that carries any moral responsibility for the effects of using the tool. For libraries, this looks like "the library offers programming and materials to everyone, and because everyone is free to choose to attend or not attend a program, or to interact with or not interact with any of the materials on the shelves, the materials themselves and the library are blameless for any of the consequences of those decisions." For the Fediverse, it's "any instance is free to defederate with any other instance for any reason, any user may block any other user for any reason, any person may fork the code and build their own version of it, and because of this, the tool itself is blameless for any of the consequences of those decisions." Ayman Mansoux and Roel Roscom Abbing's "Seven Theses On The Fediverse and the Becoming of FLOSS" explores questions of whether code and applications can truly be neutral and blameless in a world that is much more aware of how claiming neutrality is a political decision. On the library side, a robust debate has been going on for years about what library neutrality even means, much less whether or not it is a position worth taking. The American Library Association commissioned an intellectual freedom and social justice working group to come up with potential alternative ethical and practical frameworks for neutrality, recognizing that the traditional library position is much less defensible in a world where previously-suppressed voices are now part of the conversation [PDF]. There are some extra complications to this question for public libraries because there's case law and such about what a "limited public forum" like a public library may or may not restrict regarding collections, programs, and spaces, but the current question seeking answers is: What affirmative requirements do code maintainers and/or public libraries have to make their tools and collections unwelcoming to people who would use them for oppressive purposes? As we said before, taking out the trash is an essential part of maintaining a healthy network. Having a shared (likely written) understanding of what qualifies as trash and what steps can be taken at what points helps immensely toward achieving that goal, as well as signaling to interested parties what amount of work will be expected from them to make the space usable and safer for themselves.

Even with these complications and big philosophical debates, I still think it's a worthwhile endeavour to encourage and support public libraries with resources that will allow them to offer Fediverse nodes and/or accounts to their service population. Moving social media away from siloed, corporate-controlled, ad-algorithm-and-outrage driven instances into smaller and more intentionally created and moderated communities is a net benefit for everyone, keeping conversations inside their contexts and delivering more tools to users and moderators to curate their experience themselves. Public libraries have promoted themselves as places where communities can access resources they would not normally be able to afford, build communities of people with shared interests to provide mutual aid and knowledge sharing, and facilitate interactions between the population at large and their civic institutions. All of these things are possible with a public library that offers Fediverse instances and/or accounts.

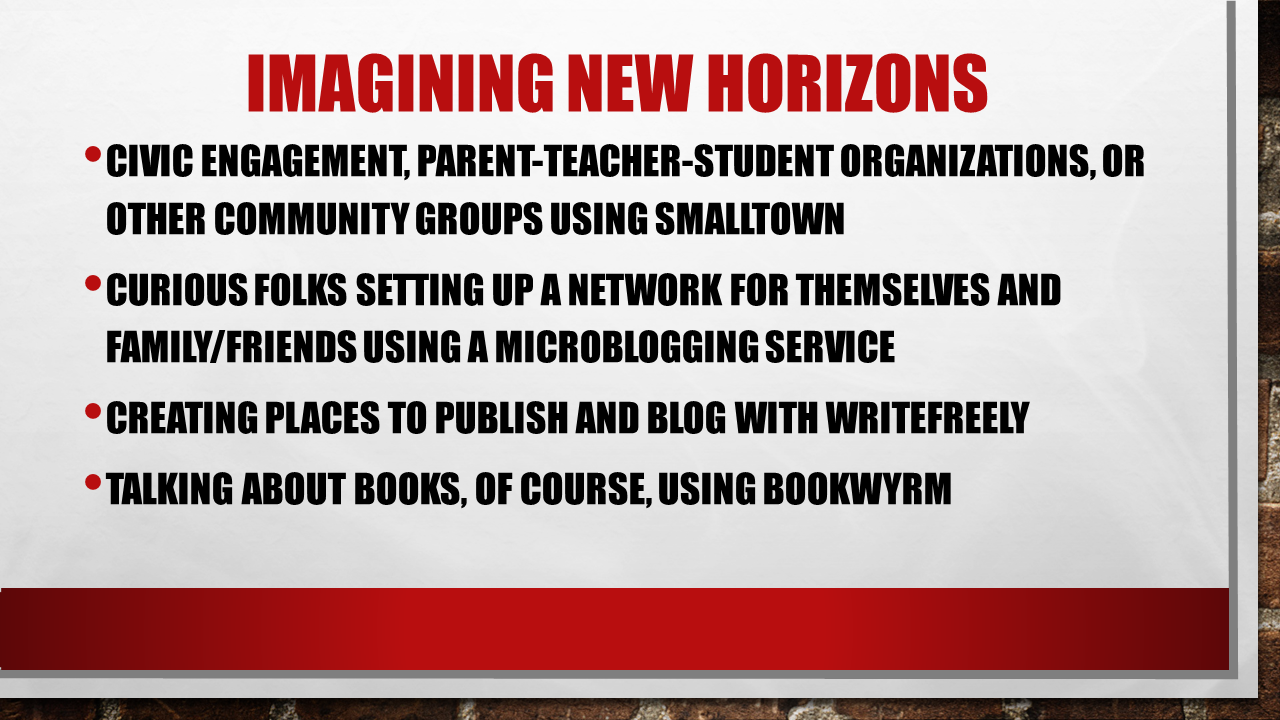

For example, a civic interest group or a city office might put up an instance of Smalltown, a Mastodon/Hometown fork with a focus on bringing local people together for asynchronous discussion of local issues, without necessarily federating with the larger Fediverse. Smalltown might also be good for Parent-Teacher-Student Organizations and Associations or other local interest groups.

Someone who's curious about code and customization, or server administration, or what it would take to moderate a network could spin up an instance for themselves and their friends and find out whether or not they like doing it enough to pursue it further, without having to put in the monetary investment and gain the large amount of prerequisite knowledge about using and administering Linux systems and web application stacks before starting.

Writers of all sorts could create blogs, newsletters, or other places to put their work and then choose who they want to share it with using Writefreely, and use the federation aspects of it to follow other writers at different instances.

And, of course, because it's a public library, there will be people who want to talk about books, so there's a good chance someone will want to put into existence an instance of Bookwyrm so that they can post their book reviews, shelves, and possibly run a book club or similar, doing the things they were doing on a now Amazon-owned platform but without giving Amazon even more of their data to be mined.

The possibilities are vast and tailorable to each community based on their interests. That's aiming for the highest promises of both federation and public libraries together. In the near future, I'd like to see more of The Fediverse @ Your Library. With your help, we can get there.